First THAB off the rank

New Zealand is in the habit of reinventing the wheel and, in our bloody-minded, NIMBY way, we have to discover our own particular culture of living closer together.1

Hobsonville, the most recent and, to my mind, the most successful suburban development in New Zealand, set cautious density goals. The master plan aspired only to increase the density from the mythological quarter-acre section of 10 dwellings a hectare to 40 dwellings a hectare – the same sort of density prevalent in the turn-of-the-century heritage suburbs of Wellington’s Mount Victoria and Auckland’s Freemans Bay. Baby steps. But steps for us, nevertheless. The completion of three- and four-storey residential in the Hobsonville retail centres has subsequently increased the overall density.

To put this in an international perspective, the minimum density in the UK for greenfield development is 50 dwellings a hectare and, in the lucky country with all that flat space, corporate developers routinely achieve 70 dwellings/hectare of gross site area (i.e. including the roads, landscape, etc.).

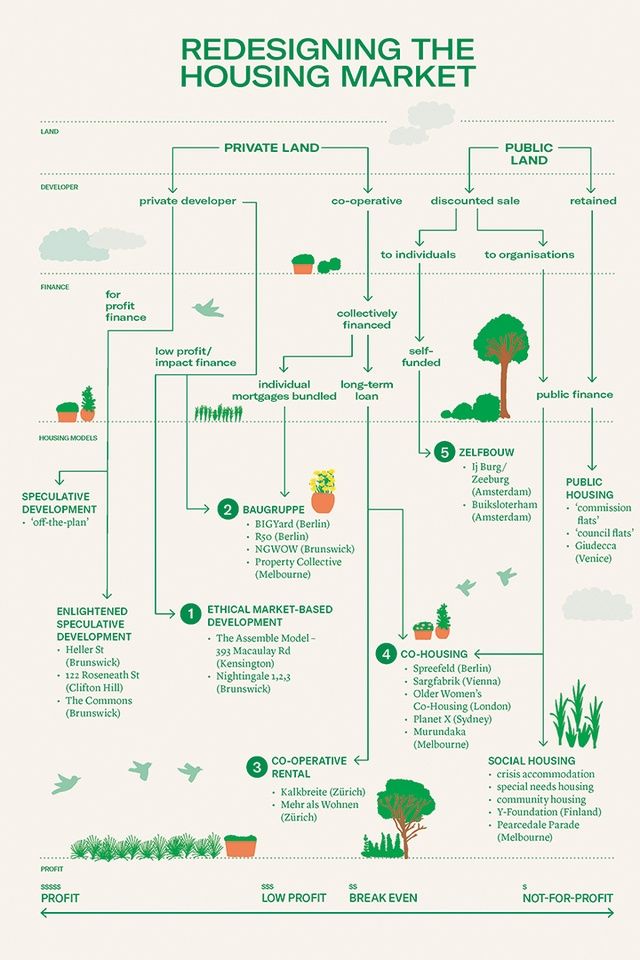

These examples of speculative housing on private land are delivered by the development industry. Melbourne urban planner and researcher Andy Fergus has summarised the broad development spectrum that spans through to state-funded public housing in a beautifully clear diagram.

Andy Fergus, ‘Redesigning the housing market’, Assemble Papers, 2019.

Interestingly, he identified that it was the housing types in the middle of the spectrum that were consistently driving innovation and pushing up the standards of social and environmental outcomes (refer development Types 1–5). Importantly, within these types, Fergus emphasises that whoever funds the development has a significant impact on the quality and diversity of housing. In contrast with the risk-averse, investor-dominated apartment market of Melbourne, the Berlin examples demonstrated the power of residents and architects coming together to shape their own living environments, without the need to prioritise financial return over liveability.

Closer to home, in our very own fast-growing central Auckland suburb of Sandringham, local couple Blair and Jules MacKinnon were determined to develop their property inheritance in a generous and more socially equitable way, “and provide the security of tenure in a longer-term rental model”.

They still needed to borrow money from the bank to replace their single 1920s’ house with 13 high-quality, low-rise rental apartments, offering guaranteed long-term tenures (with leases of up to 10 years) and median rentals based on average long-term Auckland rent growth and market valuation.

The bank needed convincing when the project didn’t forecast the standard 20 per cent developer profit returns at completion. As owners keeping the apartments, Blair and Jules were more focused on returns over the longer term. They invested upfront to provide better amenity and more common space for their residents and reduce future maintenance. In the end, the bank was satisfied with lower initial developer profit on the basis of a strong 20-year forecast that showed good returns and reliable debt reduction.

So, exactly as Fergus’ research predicted, “the ethical developers”, Blair and Jules, who took primary responsibility for the funding, waived short-term income to achieve a more socially equitable vision over an extended time period (refer Type 1 above).

By holding and leasing, they meet the steadily increasing demand for renting in New Zealand. Around 40 per cent of New Zealand households now rent: up from 28 per cent in 1999.2

And, to remove any doubt that lower house prices or increased affordability will result from increasing the housing supply (put about by the National Party most recently), please refer to research from UNSW Prof Peter Phibbs using Greater Sydney and the median dwelling price and supply as an example.3

North-facing street-side balconies overlook the comings and goings on Aroha Avenue. Image: Dennis Radermacher

Planning process

26 Aroha aspires to a European sensibility for a post-carbon transport future. It’s located close to public transport, schools and amenities. Instead of car-parking spaces (there are three rentable tenant parks), the development provides scooter and bike parking, e-bike charging points, and access to a shared electric car owned by the building.

Given the building proposal for the 900m2 site was within the new THAB (Terrace Housing and Apartment Buildings) Zone envelope (with allowable 50 per cent site coverage, 16m height and 3m-high, 45-degree setbacks), why could the planners not wave this scheme through un-notified and use it as a poster child for new building height and density – the Auckland spatial plan in action at last.

“The project was submitted before the Unitary Plan was fully operative so there were delays while Council thrashed out some of the rules in the high court,” Blair explains. “And it’s fair to say they were floundering a bit as we pushed the limits of the new THAB rules in a purely residential street right from the very start.”

“Conservatively viewed, this was a four-storey building (at one end) going up in a street of predominantly single-storey housing,” says Jasmax architect James Whetter. “The reduced car-parking was another topic of conversation, despite the THAB Zone allowing zero car parks.”

There were minor intrusions into the boundary height planes due to the sloping site, even using the alternative HIRB rules (8 metres and 60 degrees). Rubbish truck access, the removal of a tree from the street front, works within the root zones of protected trees and being within a flood plain were also cited.

Earthworks consent is separate legislation to the planning consent and, in the end, the volume of earthworks and a noise breach (from approximately four days of rock-breaking excavation) became the tipping point for a limited notification hearing by an independent commissioner. This added nine months to the project and it cost, in total, $800,000 to finally gain the RMA consent. It’s not surprising a corporate lender expects a developer to have a 20 per cent margin to manage this sort of risk.

Suffice it to say, the approvals process was protracted, and questionable, given the proposal was meeting Council’s own strategic objectives for densification.

Environmentally Sustainable Design (ESD)

There is also nothing short term or ‘ticking the green boxes’ about the ESD strategy. The MacKinnons’ approach eclipses the minimum insulation standards of the New Zealand Building Code.

Mansard walls/roofs are approximately R4.5 on average and the walls average R2.1. The envelope is ‘wrapped in insulation’ rather than insulated via infill within a stick build structure. All windows are double-glazed. Cross-flow cooling ventilation is supplemented with wall-mounted panel heating. Internal party wall blockwork is left exposed to provide thermal mass. The building is waiting for its Homestar 9.0 rating to be verified.

As well as these good passive credentials, the building is fitted out with solar hot water and photovoltaics, which supply power to the common areas. More interestingly, the MacKinnons are setting up an app that offers a single, monthly utilities bill for each tenant (which includes hot water, power and broadband fibre connection), which should save 25 per cent on the equivalent household bill.

Custom-made kitchens and bathrooms include timber recycled from the original bungalow and power-and-water-efficient appliances. Image: Dennis Radermacher

Architecture

I think being the first THAB off the rank (haw) and (I’m guessing here) undergoing an adversarial consenting process have influenced the form. To me, the project keeps its head down below the parapet. Jasmax has managed to deliver a very competent architectural solution stealthily, disguising the bulk of the building in the slope of the site and keeping the detailing unpretentious to fit more unobtrusively into the street. All the while, it achieves its very laudable 144 dwellings per hectare density and, more importantly, equitably distributes long-term amenity to a wider diversity of citizens.

Dressed in a little down-home drag and understated (always a good thing in New Zealand), 26 Aroha reminds me of Camp Glenorchy, with its recurrent forms disguising a net-positive energy tour de force driven by a sophisticated underground data centre.

What lessons can we learn?

When THAB is applied to a 60m-long site, with mandatory side boundary setbacks, then a central core typology of corner apartments relying on long hallways results, in order to provide an enduring outlook over the short ends of the site – from the living rooms to the park and the street respectively.

Arguably, this lineal typology of 50 per cent site coverage misses an opportunity for on-ground outdoor space. And, if replicated next door, this four-to-five-storey form creates potentially 16m-high canyons, with dwellings uncomfortably close to one another (refer section drawing in image 7).

In future iterations, it would be useful to explore the potential of THAB as a repeat model, in aggregate. Could the sharing or combining of adjacent properties create more mutually beneficial site layouts? For instance, the North-South-orientated side yards could be aggregated to form laneways linking to the adjacent park or perhaps 9m-wide ‘planted fingers’ could provide a green outlook to adjacent living rooms and mediate views of those facing each other across boundaries.

1. Communal organic garden. 2. Rainwater harvesting. 3. Bike and scooter parking/shared e-bikes. 4. Solar PV panels. 5. Low-waste e-truck collection. 6. Shared guest room. 7. Rooftop garden. 8. Shared laundry and kitchen. 9. Solar hot water heating. Image: Supplied

Of course, in codifying densification of our neighbourhoods, there is an associated onus on public authorities to support this closer living with complementary public open space. In the post-pandemic street, easy and equitable access for every address to quality open space is essential for social distancing, reducing the need for car travel to public parks and tracks for exercise.

The MacKinnons’ site previously held just one house (a density of 11 dwellings a hectare). Most along the street have two villas on their approximately 900m2 sites. Building 13 new apartments lifts the density to 144 dwellings a hectare – way above the five-fold density increase that New Zealand should target.

Imagine a future of aggregated THAB models that create mutually beneficial living environments. Canny owners could join together and yield common gardens and synergies with the city. We can’t rest on our laurels. The hard part is just beginning and this project is a fine start.

Footnotes

1. Andy Fergus, with illustration by Alice Oehr, ‘Redesigning the housing market’, Assemble Papers, 2019. assemblepapers.com.au/2019/02/21/redesigning-the-housing-market/

2. Stats NZ.

3. Prof Peter Phibbs, the ‘Phibbs Line’, UNSW.

4. Janette Sadik-Khan, ‘We must rethink our streets to create the six-foot city’, The Guardian, 4 Sept 2020.

Indonesia

Indonesia

New Zealand

New Zealand

Philippines

Philippines

Hongkong

Hongkong

Singapore

Singapore

Malaysia

Malaysia