Stadia dreams

In Los Angeles, a new home is being built for the Rams and Chargers NFL teams. With a maximum capacity of more than 100,000 (70,000 excluding standing-only sections), the Los Angeles Stadium at Hollywood Park (naming rights to be determined) is far more than just a place for sports; it’s part of a larger 298-acre brownfield redevelopment that includes entertainment, office, retail and residential buildings.

I have recently stood outside the massive site where the stadium is being constructed and spoken with its architects, HKS, and the aspect of the stadium that most impressed me was the way in which it will become the hub of a thriving community. Sharing its giant roof form is a 12,000-seat theatre, which may host the next Academy Awards. It’s on major transport routes. The light and airy design also includes a small lake, palm trees and plenty of seating for use when there are no games on.

The stadium is the jewel in this comprehensive mixed-use development that includes apartment and office buildings for thousands of residents and workers. With its surrounding community, the stadium will be an integral part of the wider city. You can see Los Angeles striving to make something urban here.

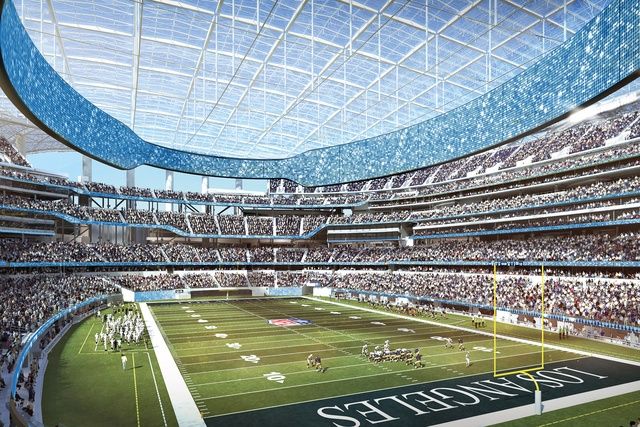

The stadium at Hollywood Park has a maximum capacity of more than 100,000 people. Image: Rick Gunter

There is a sense of awe and wonder that this grand, privately financed NZ$3.2-billion dream is coming to life (although Los Angeles city will receive US$25 million per year, plus tax revenues and aggregation benefits).

Many unique features define the Los Angeles Stadium at Hollywood Park. The stadium itself is half-sunken into the land; this is likely to reduce seismic loads for the cantilevered roof support pilotis. It includes a two-levelled, 2.5-acre porte cochère. And it has an extraordinary, wafer-thin roof made from ETFE (ethylene tetrafluoroethylene) – a self-cleaning, durable and recyclable plastic material, which also provides sun protection.

Sun protection is as, if not more, important in New Zealand, too. And, as the architects for the proposed new waterfront stadium in Auckland, Peddle Thorp decided to roof the stadium early in the design process. Rugby players may be happy playing in the wet, and, bless her, Adele made a brave show of doing the same, but we imagine that most Aucklanders do not enjoy the experience of going home soaked and cold.

We believe the proposed waterfront stadium will add a vital asset to Auckland, which must, as a competitive international city, have the big assets: museums (art and culture), conferencing, and sports and entertainment venues. The big play here (and what pays for this free-to-rate-and-tax-payer proposition) is what we call ‘Bledisloe Quarter’; a mixed-use development that, like Wynyard Quarter to the west, would bookend the city to the east, housing thousands of residents and working Aucklanders. And, like the Los Angeles Stadium, the waterfront stadium would be connected to the greater Auckland city by a multi-mode public transport network.

Beyond the Los Angeles Stadium, we visited the West Coast of the United States and Japan to compare and contrast our stadium design with built models overseas. We wanted to consider what makes a modern stadium work, from an attendee point of view, and, also, what the latest trends are in stadia, including their use of digital technology and their sustainability.

We chose Japan because it is the home of the Rugby World Cup this year and we wanted to see how the country’s preparations were coming along in adapting its collection of 12 legacy 2002 FIFA World Cup stadia.

We chose the United States as the country for new, mixed-use, privately funded stadium developments, featuring all kinds of innovation.

In Japan, the stadia we visited were mostly at the edges of the cities. The buildings that were constructed for the FIFA World Cup have been constantly in use.

Compared to most current United States stadia, Japanese versions are more traditional in style. None have fixed roofs and none are situated in mixed-use developments. But the main advantage the Japanese stadiums have is access to a wonderful public transport system – the famous fast trains which allow fans from across the country to reach these often-remote stand-alone buildings in comfort and ease. An outstanding example is the Shizuoka Stadium Ecopa in Shizuoka Prefecture; it is situated in a beautiful location amongst the hills and trees and, like all of Japan, exquisitely maintained – as if the concrete had been made yesterday.

Pictured:The Toyota Stadium features a retractable roof.

We spoke to managers at the Shizuoka Stadium and the Toyota Stadium. They were excited about the Rugby World Cup and were expecting high attendance – 30,000 and more per game.

We saw seven stadia in Japan and the designs of the buildings ranged from satisfying to beautiful. The most beautiful ones have that delicacy that only the Japanese can achieve in concrete and steel: buildings in the round, holding to a rigorous structure and geometry. Even almost two decades after they were built, they are still exquisitely finished and maintained, with not a trace of tagging or chewing gum.

A unique and loved exception, to those located away from city centres, is the Nippon Budokan in Tokyo and this exception is illustrative. Budokan was originally built for the 1964 Summer Olympics as the judo competition venue. Just two years later, in 1966, The Beatles played the Budokan. To most outsiders, its reputation is for the concerts – who hasn’t played the Budokan? And if not, why not? Integrated into the city, roofed and accessible, it thrives.

Compared with the United States, stadia in Japan don’t give great emphasis to retailing or food and beverage. This may be due to the time the games take; each NFL game is a four-hour process, with each play averaging seven seconds. Football, like rugby, is still a ‘game of two halves.’

The Americans understand that the competition for game attendance is a 60˝ TV, a couple of armchairs and a six-pack. They embrace that competition by filling every moment with entertainment and by making the stadium a wonderland of digital technology and personal service. In the Rams’ new home stadium in Los Angeles, no two concourse areas are the same; the experience at all faces and levels is hugely varied – a ‘Tower of Babel’ with food and beverage. The interior is populated by boutique corner bars selling food and drink – franchises, all trying to outdo each other. Coordinated by one master contractor, the result will offer variety for attendees; for instance, there will be Mexican and South American restaurants, a wine bar, cafés and much more.

But there’s more (there always is in the United States): the digital experience. The Los Angeles Stadium architects explained that, with less than a year to completion, a decision on digital formats was still to be made. There’s a sense that, remarkably, 5G may soon be redundant.

The US$1.4-billion Chase Center stadium in San Francisco opened in September.

Like many new stadia, the Rams’ new home has a huge digital screen ‘donut’ that hovers over the field. It seems that almost every flat surface in the stadium – spandrels, fascias, etc. – is a screen. Every square inch is for sale. And it’s smart, too – when you’re waiting to order your craft beer or margarita, the menu board will scroll the play on the field as it recommences so you’re never missing out.

The seating is also extraordinary. Almost 60 per cent of the seating appears to be in boxes, from the usual midfield glory box to boxes at field level, right there with the players. It’s a reminder of just how big the United States is; there was no trouble selling all the boxes and the seats, and there is still a 30,000-person waiting list.

Efforts to diminish car use are evident in California as seen in the progress of light rail projects in both Los Angeles and San Francisco. Innovation plays a big part: provide 10,000 car parks? No way. But the Los Angeles Stadium will provide some parking (no more than 1000 spaces on site) and utilise the existing parking in the properties nearby. It’s not as easy as is laying down the black stuff but it’s much more effective commercially and better from a sustainable, urban design point of view.

Like the Los Angeles Stadium, the 18,064-capacity San Francisco Chase Center is the hub of a privately developed, mixed-use area, comprising office and retail space and a public plaza. It sits within a wider waterfront district of restaurants, cafés, offices and public recreation areas. The Center opened on 6 September this year and, for once, traffic jams made the news for the right reasons – there were none. Instead, fans pedalled, trained, scootered and bussed to the venue. Indoors, too, the Chase Center will host music and cultural events. For the cyclists out there, check out the bike concierge.

We viewed 14 stadiums in total during our short time away. We came home feeling as though we had witnessed the evolution of stadia, from the traditional, elegant Japanese buildings to the multi-use, digitally inspired American versions.

As it is planned, we believe there would be nothing in the world quite like our harbour’s edge sunken stadium and we were encouraged to see that we had unknowingly imitated aspects of many successful modern overseas venues. Multi-use stadia, in mixed-use developments, privately funded, closely located and integrated with the existing city, utilising existing and spurring further urban infrastructure, are the future. To endure, our proposed stadium would need to be like the 57-year-old Budokan: urban, integrated, enclosed, multi-use and loved.

This article was originally published on ArchitectureNow

Indonesia

Indonesia

New Zealand

New Zealand

Philippines

Philippines

Hongkong

Hongkong

Singapore

Singapore

Malaysia

Malaysia