Houses Revisited: Le sublime

My luggage was lost en route from Wellington to Blenheim. And I’ve never been so relieved. It meant I didn’t have to lug my roller suitcase up the steep logging track that wound from the beach, up the hill and around the point to Turn Point Lodge. To say this house is remote is an understatement. The 20-minute uphill tramp comes after a 40-minute boat ride through the Marlborough Sounds, and a meandering drive from Blenheim before that. With no jetty, and no possibility of building one in the future, the boat moors at the beach, and visitors must make an intrepid jump from deck to shore. The skipper then anchors the boat off shore, and kayaks back in.

But when you arrive, all that’s forgiven and forgotten. The muddy incline, the gusty boat ride – all of it ebbs away when you’re confronted with the view. I find myself struggling against the urge to harvest a crop of flowery adjectives, like “magical”, “sublime”, “enchanting” … Quite simply, this is our idealised (and idolised) New Zealand: untouched; serene; picturesque.

The site’s isolation is part of it; apart from mussel boats heading out early in the morning and evening, the only evidence of habitation are bird noises and earth bruised by the ruttings of pigs, wild deer and possums. In the midst of this isolation Turn Point Lodge balances on a steep ridge overlooking nikau. The house is a retreat for two French brothers; like the bush around it, it’s surprisingly imprinted with signs of life. The very forms of the buildings and their arrangement offer a sort of anthropomorphic diagram of the owners’ lives here.

With the site as it is and where it is, perched above the water, far from the boat mooring with no walking tracks except the logging road behind, and no beaches to nip down to, the house becomes everything. To avoid stir-craziness, the house had to accommodate the brothers together but allow them time apart; it was required to be able to grow with them if they have families, and to adapt as quickly as the weather shifts.

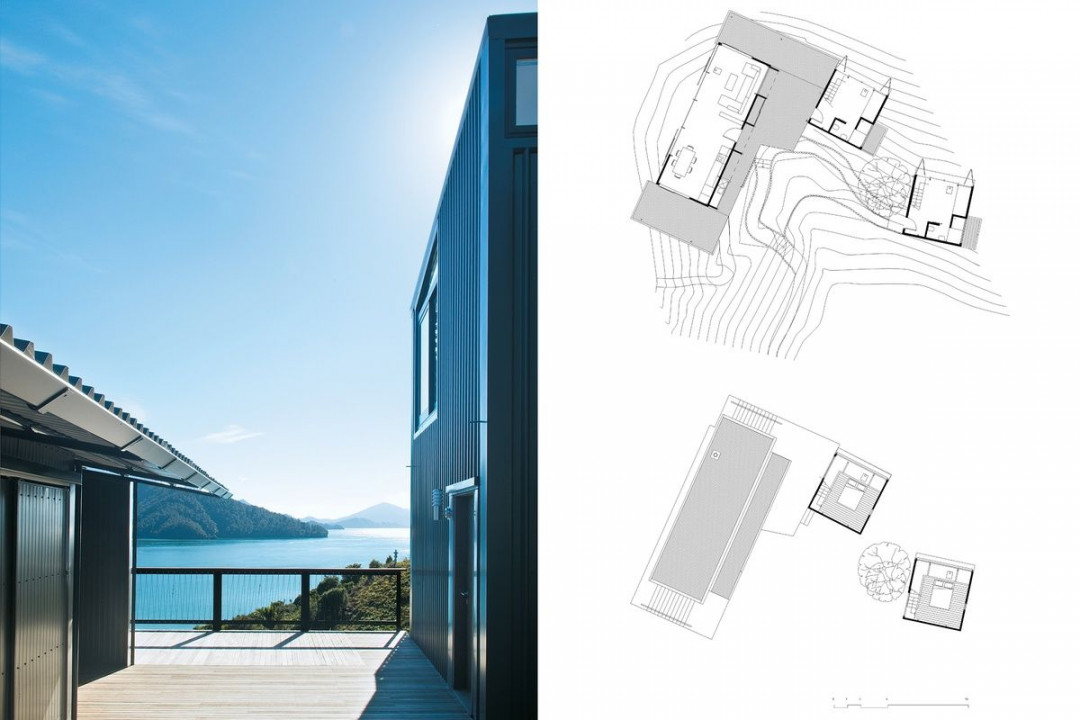

The solution is three separate buildings: two squat towers, one for each brother, that nestle into the hill and look down the Sound; and, in front of these, a long, shipping container-like pavilion which holds the kitchen, dining and living room. Outdoor decks connect each building, often forcing a confrontation with the weather on the way to bed, but moving between inside and out also makes the place seem larger.

Access became a very significant design issue here. With no real boat access, and therefore limited ability to get diggers or machinery onto the site, the three buildings and structural sub-floor frames were built off-site and heli-lifted into position. As well as basic weathertightness and wind load considerations, the units were constricted by the need to keep the weight of each under 4.5 tonnes – extremely light for a building – and to remain structurally rigid to withstand flight. Steel, very early on, became the structural material of choice. Aluminium because of its robustness, lightness and low maintenance, was chosen for the cladding. The interiors have been lined in white painted plywood with a negative detail at each seam emphasising the house’s piece-meal, jigsaw-like construction.

Construction, the actual assembly of building components, became the driving force for the design. Even the usually prosaic construction of foundations became a highly choreographed operation. Very little of the ground has been altered. The house is perched above the ridge on a steel foundation plinth, rather than being excavated – to any extent – into the earth. To set the foundation into the ridge, Hugh Tennent had micro-piles driven into the ground. The concrete pile caps were then located exactly with GPS, and those co-ordinates were used by the steel manufacturer to produce the foundation platforms. As with the units themselves, this entire steel platform structure was flown onto site and lowered onto the piles, making a readily assembled flat deck.

Once the foundation deck was in place, the initial idea was to drop the finished buildings onto site, complete, thereby minimising the trades on site. As the weight began to add up, despite careful planning and weighing of all components, the units reached their maximum weight just after the shells were enclosed. This meant that the majority of the internal and finishing work still had to be completed on site. Builders were accommodated for three months in the next bay and boated to work every morning. Building materials were loaded into a 4-wheel drive, bought specifically for the purpose, transported along the precarious track to the house, and then wheel-barrowed down a narrow path.

And yet, in spite of the numerous readily available and justifiable excuses such an isolated and difficult site may have provided, the finish on Turn Point Lodge is near immaculate. The detailing is what makes this building work cohesively. The architect has focused attention on every minor element, as well as the whole, an approach that elevates three relatively simple units to an integrated, crafted house. In the living pavilion, the steel structure is exposed giving a rhythmic staccato effect.

Similarly in the studio towers, steel details such as the folded stair help to demarcate the small space and create interest. Custom-folded gutters and a pipe support structure for the pavilion’s rear overhang hint at the thoughtfulness that has gone into every element. To soften the industrial feel warm, sustainable timbers have been used throughout. The saligna floor has been crafted like a piece of furniture, with exposed butt ends and peg holes finished with timber inserts and buffed smooth.

Turn Point Lodge is a small house, but one that has been, in acknowledgement of the site’s many difficulties, thought through very carefully. Each of the studios is well planned and has ample storage, and storage space is also abundant in the living areas and in horizontal rampart-like bays along the rear of the pavilion. On this project, nothing has been taken for granted. Every length of pipe, every path that has been made and every stone set in place, has been considered as part of the whole.

It may have been economics and the need for spatial efficiencies, as much as aesthetics, that demanded such thoughtfulness, but the care that is obvious in every detail has produced a house that is simply beautiful.

Indonesia

Indonesia

Australia

Australia

New Zealand

New Zealand

Philippines

Philippines

Singapore

Singapore

Malaysia

Malaysia