Why Timber is Number One in Japanese Architecture

Traditional Japanese houses have boundless appeal, for their elegant shapes and how they seamlessly integrate with their surroundings. Over centuries, craftsmen developed advanced woodworking techniques. Incredibly, a large portion of traditional Japanese buildings that exist currently have stood for hundreds of years, and the oldest wooden building in the world still stands in Nara, outside of Osaka. This article will briefly examine the history of Japanese woodworking, and how Japanese carpenters and builders used advanced techniques to erect long-standing structures that were easy to build and replicate, and resistant to environmental effects.

The main building and 5 storey pagoda of Horjuji temple was built in 600 AD, making it the oldest wooden building in the world.

To understand the purpose and form of Japanese architecture, it’s important to understand the geography and climate of the country. Japan is an archipelago comprised of almost 7000 islands, although less than 300 are inhabitable. It sits off the coast of mainland China and Korea, and both nations are a great cultural influence to Japan throughout history due to extensive trading. Japan is also directly on top of the Ring of Fire, making it extremely susceptible to earthquakes and tidal waves. On the mainland, mountainous regions have made space extremely tight and difficult to navigate. However, these conditions have meant invading Japan was a nigh-impossible feat, allowing Japanese artisans to hone their techniques.

As Japan continued to develop, so too did new construction challenges appear. Out of utter necessity, the Edo period (1601 - 1867), named for the capital city, now called Tokyo, was when traditional Japanese architecture was perfected. Edo was hit by 49 major fires during this period, wiping out large areas of the city each time.

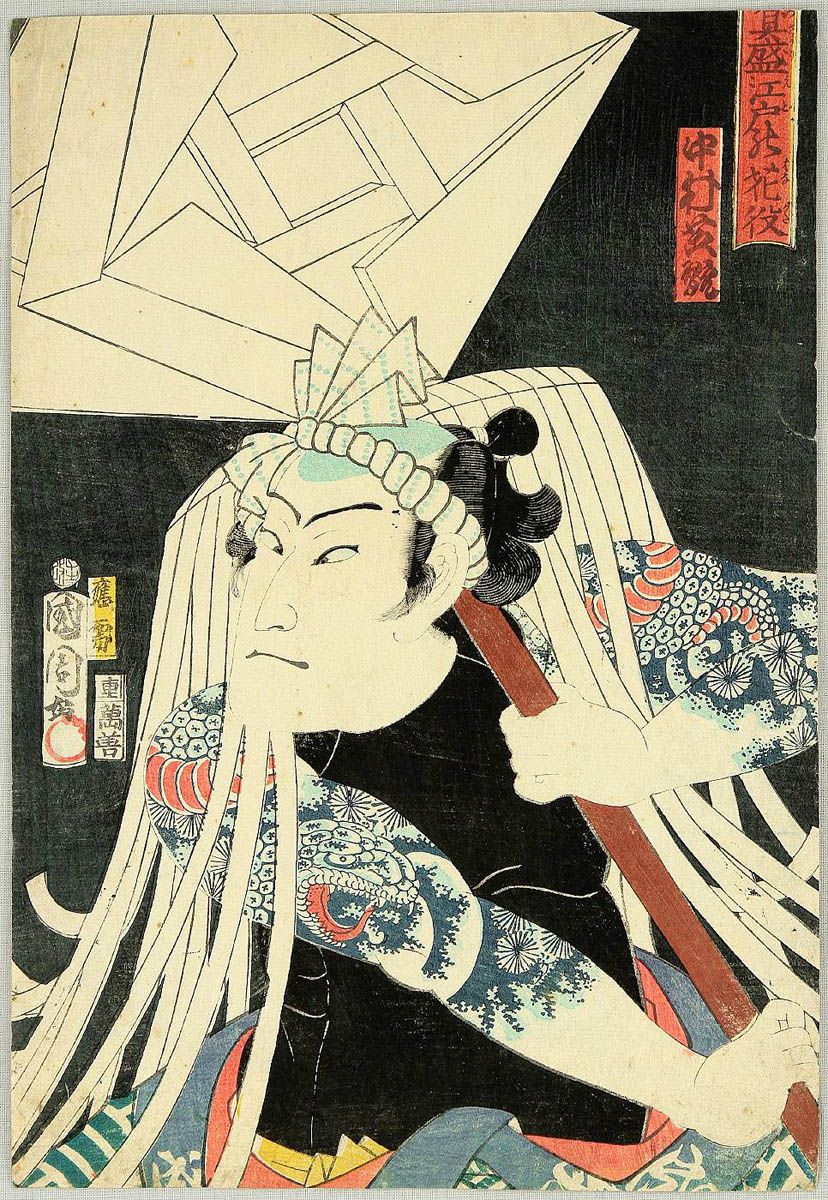

Edo Fireman by Kunichika Toyohara (1835-1900)

The frequency of the fires compared to other regions was mainly due to density; Edo grew as a city due to unification, with many people leaving the countryside for economic reasons.

Fire was an everyday part of life, used for cooking, heating and for sealing timber. In fact, fires were so frequent that, according to scholar Matsunosuke Nishiyama, citizens of Edo saw the fires as “inevitable”, and were content as long as their actions didn’t cause it.

Fire meant fast and easy construction and repair of buildings was a necessity. During this period, techniques of proportioning and prefabrication were adopted, allowing for rapid erection of new buildings. Construction efforts were streamlined, from the lumber yard to commencement, in order to counteract the frequent fires that threatened the city.

Earthquakes, flooding and lack of space are all environmental elements that Japanese builders mastered. Japan is a highly forested region with difficult terrain, so it’s almost essential that building materials were a majority timber. Japanese craftsmen took time to understand wood and its properties, taking advantage of difference in variation, in order to make the strongest building material possible. Sustainability was an intrinsic part of construction, and daily life overall. Buddhist and Shinto traditions insisted on a strong connection to nature, ensuring nothing more than necessary was used, and the form of the materials are respected.

Timber posts are connected at right angles, using advanced joinery techniques. Wood is cut precisely to create complicated mortise-and-tenon joints, with wooden pegs used to keep it in place. This wood joining technique and lack of metal allows the structure to be extremely flexible, giving it strong resistance to earthquakes and allows it to expand in wet conditions. Another benefit of this method was that it is “reversible”, meaning individual elements can be taken out and replaced quickly, making repair simple and easy. They were often raised several feet off the ground to allow for ventilation.

A classic example of a tenon-and-mortise joint.

Woodworking tools used by Japanese builders were also quite different to their European counterparts. Looking something like a saw crossed with a machete, nokogiri saws are designed to cut on the pull motion. The blades are thin and cut with precision but, unlike western saws that require power to cut efficiently, nokogiri saws requires skill and technique to cut effectively. Pull strokes allow for more control over the blade and requires less effort. The nokogiri saw cuts the wood thinly and accurately, and is the foundation for Japanese wood architecture.

The nokogiri cuts on the pull motion and has smaller teeth, allowing for higher precision cutting.

Another aspect of Japanese craftwork is that the skill of a designer is honoured rather than the structure itself. This emphasis on ability of the individual means that high quality of product is maintained, and encourages new generations of crafters. This is exemplified in Japan’s Living National Treasure program, that honours designers, artisans and masters that have contributed greatly to their craft.

UK designer Hugh Miller noted five overarching philosophies in Japanese carpentry. The first he describes as the “absence of noise”. This refers to Japanese carpenters use of advanced mortise-and-tenon techniques to hide joinery, maintaining the form of the materials.

The next element he described is an emphasis on maintenance. This is seen in other areas of Japanese culture, such as the tradition of repairing ceramics with gold. Instead of resisting maintenance, carpenters have embraced it. As previously mentioned, traditional Japanese houses are designed so parts can be replaced easily, which is important due to wet conditions causing wood to rot. This also means that it is necessary for craftsmen to pass down their knowledge.

The third element is “lightness”, which can be summarised as using the minimum amount of materials needed, and designing a structure to fit in with its surroundings instead of standing out. The last two factors are “innovation”, experimenting with material shapes and form was common, and “harmony”, which is an accumulation of all these elements in balance with its surroundings.

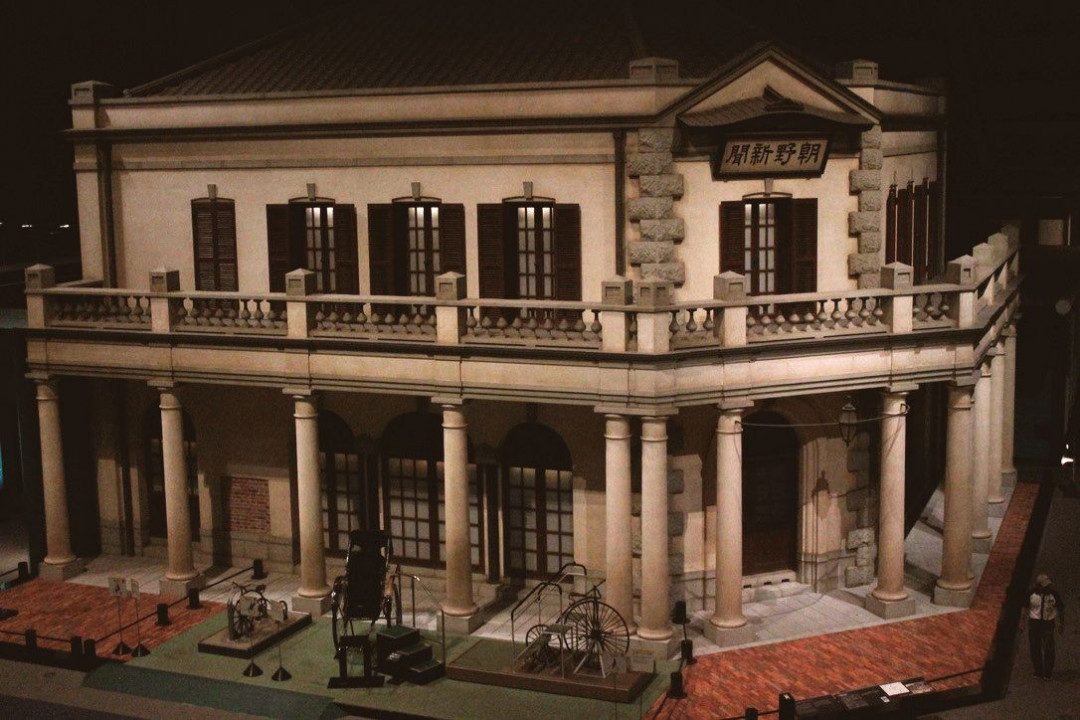

A full-scale replica of the Choya newspaper company at the Tokyo Edo Museum.

There's no limit to the appeal of Japanese architecture and it's intrinsic link to culture, history and the environment. All of these elements contribute to the harmonious form and synchronicity of Japanese timber structures. When Japan opened its borders during the Meiji period, it Japan began adopting European architectural styles and materials, like steel and concrete, after opening their borders during the Meiji period. This shift was more rapid post-1945, after Tokyo was repeatedly devastated by Allied firebombing campaigns and the nation was occupied by Western forces. However, traditional methods are still highly respected and practical in Japan, many structures and buildings have been painstakingly restored to their original appearance by craftsmen using traditional methods. The respect for nature, form and sustainability, and an emphasis on skill and technique are facets of Japanese architecture that are high transferrable, and should be adopted worldwide.

Indonesia

Indonesia

Australia

Australia

Philippines

Philippines

Hongkong

Hongkong

Singapore

Singapore

Malaysia

Malaysia