Review: Christchurch Architecture: A Walking Guide

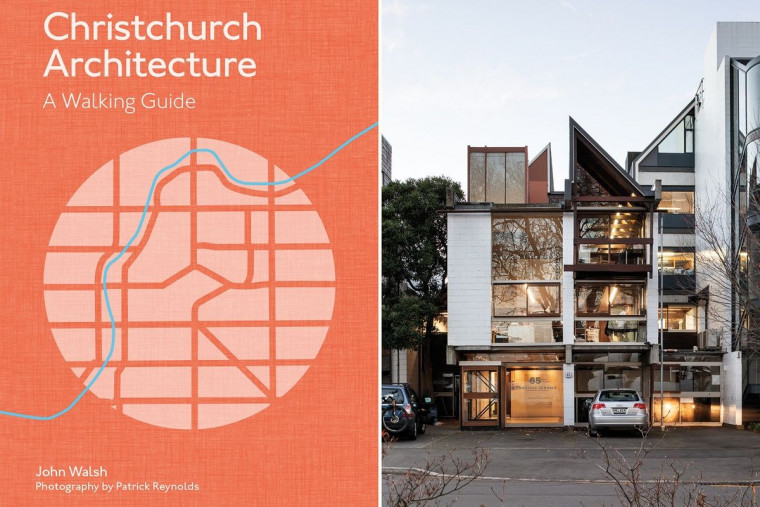

Christchurch Architecture: A Walking Guide by John Walsh and Patrick Reynolds, Massey University Press, 2020; Warren and Mahoney’s 65 Cambridge Terrace.

While another recent book about Christchurch architecture, I Never Met a Straight Line I Didn’t Like, reveals what is inaccessible to the public eye, John Walsh’s Christchurch Architecture: A Walking Guide is a tour of buildings that can be seen and, mostly, entered from the footpath. With a focus on the centre bordered by the ‘Four Avenues’ (Bealey, Fitzgerald, Moorhouse and Deans), as well as the Ilam Campus of the University of Canterbury, significant buildings have been chosen and masterfully divided into six walking routes alongside colour-coded maps. This book is for any wanderer of Christchurch, whether familiar or unfamiliar with the streets.

Buchan Group’s Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū.

An updated guide was sorely needed after the damage done by the 2010-11 Canterbury earthquakes and this directory is rooted in the reality of what remains. Those who did know Christchurch before the quakes will lament buildings not included – amongst those the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament (I have driven past recently and seen the crews, hard at work clearing the site). Yet Walsh reveals what fluency remains in a broken story. Sixty outstanding buildings have been included: the brand-spanking new in familiar company with the early stone Gothic Revival masterpieces.

Each of the buildings selected is remarkable in its own way but not without controversy. Te Omeka Justice and Emergency Services Precinct (designed by Warren and Mahoney Architects, with Cox Architecture and Opus Architecture) contains all justice and emergency services, indifferent to the principle that the courts and police should be, and must be seen to be, separate. Walsh unabashedly acknowledges such wrangles in the clear and concise accounts that accompany each building, capturing some of the difficulty Christchurch has been through in its journey thus far. The photographs capture the buildings in their current states, with some still in ruins (though proposed to be rebuilt), such as the Municipal Chambers, 1887, by Samuel Hurst Seager. Despite the politics of the Christchurch rebuild, the guide presents mostly optimism about the city’s future.

Architectus, Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects and Matapopore Trust’s Tūranga Christchurch Central Library.

One such area for hoped improvement is inclusiveness. There have been many opportunities for significant work in Christchurch in the past decade; however, as Walsh writes, this guide is a ‘chronicle of the works of white males’. While it is true that the architectural teams may have been led by white males, what is not mentioned is that these buildings are collaborations involving many different faces. This is a small but not insignificant step, with much work still needed to bring talent to the top, regardless of sex and race. On a different but more positive note, some of the virtuosity of the 1950s–1970s can be glimpsed in the bold, brash post-quake buildings, and these are ready to serve and inspire all mankind.

Whether you are a resident of Christchurch or a visitor, Walsh’s pocket-sized guide will carry you merrily and educationally through the streets with its insight, quirk and humour. Christchurch’s built fabric is ever-changing but Christchurch Architecture: A Walking Guide makes for a worthy bookmark in its history and signals a hope that more people will be inclined to learn and value the great architecture, old and new, of Christchurch.

Indonesia

Indonesia

Australia

Australia

Philippines

Philippines

Hongkong

Hongkong

Singapore

Singapore

Malaysia

Malaysia